This year we are focusing on 1920s Alhambra. In this issue, we shine the spotlight on three 1920s-era buildings that are still standing in Alhambra and retain many of their defining characteristics, almost a century after they were built.

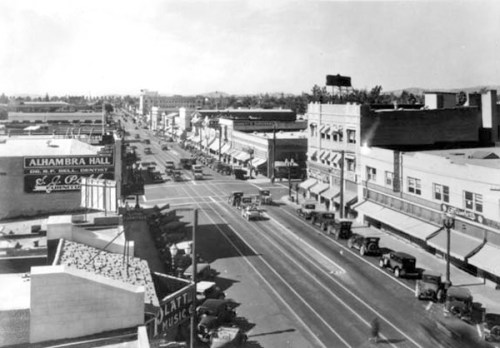

Architecturally, the 1920s introduced Art Deco, Neo-Gothic, and Beaux-Arts and many other styles of architecture to the world. It was no different in Southern California. Here in Alhambra, the Roaring Twenties was a time of tremendous growth and change as our young city welcomed a huge influx of new residents and businesses; a decade in which the local population tripled in size. It was the Jazz Age, when “Anything goes!” was the mood and everything seemed possible. Construction exploded and Alhambra saw the design of buildings that ranged from a Carnegie-funded Greek Revival-styled library to an Egyptian-themed movie theater. Sadly, many of these 1920s-era buildings have either been razed or altered beyond recognition.

Despite significant losses through the decades, Alhambra still has a number of outstanding examples of 1920s-era architecture. These buildings should be preserved, protected and celebrated. The Granada, formerly the LA Gas and Electric Corporation headquarters; the Carmelite Monastery on Alhambra Road; and The Alhambra, formerly the C F Braun & Co. headquarters, are shining examples of how the architecture of the 1920s touched the lives of Alhambrans a century ago and how that architecture still influences us today.

The Granada, formerly the Los Angeles Gas and Electric Corporation

Constructed in 1929 at a cost of $160,000, the building was designed by LA Gas Company architects and engineers to evoke the period of the Italian Renaissance. Arched window and door openings predominate, with a glazed terra cotta base surmounted with varied-colored brick in harmonizing shades.

Constructed in 1929 at a cost of $160,000, the building was designed by LA Gas Company architects and engineers to evoke the period of the Italian Renaissance. Arched window and door openings predominate, with a glazed terra cotta base surmounted with varied-colored brick in harmonizing shades.

On September 7, 1929 the company held an “open house” at its handsome new office building. The public was invited to visit and to view the beautiful new offices. Music was furnished for the occasion by the company’s own orchestra, comprised entirely of Gas Company employees. Refreshments were served, and Manager Roy C. Gardner was on hand to greet the public as host of the gala event.

Newspapers of the day raved about the impressive design and architecture of the building. The first floor contained the main lobby and corporate business offices, manager’s office, investigation room, vault, and distribution department offices.

Newspapers of the day raved about the impressive design and architecture of the building. The first floor contained the main lobby and corporate business offices, manager’s office, investigation room, vault, and distribution department offices.

Of beam and girder design, the interior featured floral decorations in pastel shades ornamenting the soffits and molds of the beams. In the northeast corner of the lobby was an enormous fireplace with a mantle of onyx inserts. The frontage on 1st Street was divided into large display windows, which were flood-lighted for the display of various household gas appliances. The main public stairs leading to the mezzanine floor featured a balustrade of ornamental ironwork. A mezzanine bordered the south and west walls and served as the display and demonstration area for the new gas- and electric-powered household appliances. The woodwork and doors on the first and mezzanine floors were of mahogany, as was the main public stairway leading to the second floor.

At one end of the lobby, a raised platform showcased the installed, fully equipped model tiled kitchen whose purpose was to introduce the public to the uses and benefits of natural gas, “The Modern Fuel.” The demonstration kitchen at the Los Angeles Gas and Electric Corporation was in frequent use as the venue for cooking classes and “household expositions” conducted by Florence Austin Chase, a nationally-known authority on home economics who also wrote a “women’s column” in the Alhambra Post-Advocate.

The Gas Company maintained offices at this location until 1965 when the building was sold to the West San Gabriel Valley Chapter of the American Red Cross. Today it is The Granada, a dance studio, nightclub, and event facility.

The Carmelite Monastery

The Carmel of St. Teresa in Alhambra was established in 1913, when five Carmelite Sisters left St. Louis, Missouri to establish a cloistered monastery in the Los Angeles area. Led by their Prioress, Mother Baptista, they lived in rented houses for 10 years until the present monastery could be built in Alhambra—the first one of their order in California. The cornerstone for this building was laid in June of 1922, with members of all Catholic orders in the Los Angeles area present at the ceremony.

A dignified Mediterranean Renaissance Revival building clad in red brick and capped by gabled roofs of red clay tile, the residence and sanctuary reflect their inspiration—cloistered European convents of the 16th and 17th Centuries. An outstanding example of  this type and style of architecture, the convent was described in the Pasadena Post upon its opening on June 24, 1923 as “one of the finest in the United States”. A classically articulated portal of pre-cast concrete defines the monastery’s entrance. The first floor of the convent is defined by loggias at the south and west elevations, which overlook a broad expanse of lawn and garden.

this type and style of architecture, the convent was described in the Pasadena Post upon its opening on June 24, 1923 as “one of the finest in the United States”. A classically articulated portal of pre-cast concrete defines the monastery’s entrance. The first floor of the convent is defined by loggias at the south and west elevations, which overlook a broad expanse of lawn and garden.

The convent’s sanctuary faces Alhambra Road. Reached by two flights of shallow steps, the entry is framed by columns that are surmounted by a classical entablature, consisting of an elaborately molded architrave and frieze and a broken scroll pediment. The name of the convent is chiseled into the frieze. Centered above the entrance, a deeply inset circular window is adorned by a quatrefoil reveal of cast stone. This site, at the corner of Monterey Street and Alhambra Road, was selected for the convent because of its particular beauty. Originally an orange grove, the site’s location provided an unrestricted view of the San Gabriel Mountains to the east, with snow-capped ranges just beyond.

Alhambra’s Carmelite Monastery was designed by one of Southern California’s most prominent architects. John C. Austin was born in England in 1870, immigrating to California in the 1890’s. He established an architectural practice in Los Angeles in 1895. Austin was very active in local civic affairs, serving as President of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, the Southern California Historical Society, and the Jonathan Club, as well as the California Board of Architectural Examiners. He designed some of the most famous and easily-recognized landmark buildings in the Los Angeles area, many of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Among these distinguished buildings are the Los Angeles City Hall, the Shrine Auditorium, and the Griffith Observatory.

Alhambra’s Carmelite Monastery was designed by one of Southern California’s most prominent architects. John C. Austin was born in England in 1870, immigrating to California in the 1890’s. He established an architectural practice in Los Angeles in 1895. Austin was very active in local civic affairs, serving as President of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, the Southern California Historical Society, and the Jonathan Club, as well as the California Board of Architectural Examiners. He designed some of the most famous and easily-recognized landmark buildings in the Los Angeles area, many of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Among these distinguished buildings are the Los Angeles City Hall, the Shrine Auditorium, and the Griffith Observatory.

The Alhambra, formerly the C F Braun & Co. Headquarters

Carl Franklin Braun, the founder C F Braun & Co. was a man who was always looking forward. Born in Oakland, CA in 1884, the son of California pioneers of Swedish and Danish descent, Carl Braun grew to be a man of many talents — an engineer, a salesman, a bibliophile, a teacher and an author. He studied mechanical engineering at Stanford University and started C F Braun & Co. in 1909 with a few associates and $500 capital. His firm would go on to become a 20th century leader in petro-chemical engineering, making substantial contributions to the World War II effort by working around the clock to build plants that produced aviation-grade fuel and synthetic rubber.

C F Braun & Co. moved its international headquarters to Alhambra from San Francisco in 1921. The complex included towering brick walls, 22 buildings and a landscaped plaza on 36 acres. The primary building material for this “modern office complex” was brick – all purchased from the same San Francisco manufacturer. Braun was a practical man, an engineer, who didn’t hesitate to move or modify buildings — or to build new ones — according to the nature of the work in which the company was involved and the functional needs of its various manufacturing projects. The significance — and the beauty — of this campus is that, through dozens of modifications and 92 years of operation, purposeful attention to architectural character and detail has preserved the integrated whole.

C F Braun & Co. moved its international headquarters to Alhambra from San Francisco in 1921. The complex included towering brick walls, 22 buildings and a landscaped plaza on 36 acres. The primary building material for this “modern office complex” was brick – all purchased from the same San Francisco manufacturer. Braun was a practical man, an engineer, who didn’t hesitate to move or modify buildings — or to build new ones — according to the nature of the work in which the company was involved and the functional needs of its various manufacturing projects. The significance — and the beauty — of this campus is that, through dozens of modifications and 92 years of operation, purposeful attention to architectural character and detail has preserved the integrated whole.

C F Braun & Co.’s interior offices featured wood paneling and were “pleasingly appointed and well-lighted” as described in a promotional brochure. It had every amenity needed for a modern manufacturing plant including a state-of-the-art engineering library, woman’s lounge, men’s locker room, a restaurant and a medical office staffed by an on-site physician. Mr. Braun’s goal was to “provide comfortable and pleasant surroundings for its workers, of every class, that they may have pleasure in their work and pride in their plant and product.” He took a great deal of pride in the “modern workplace” that he created.

C F Braun & Co.’s interior offices featured wood paneling and were “pleasingly appointed and well-lighted” as described in a promotional brochure. It had every amenity needed for a modern manufacturing plant including a state-of-the-art engineering library, woman’s lounge, men’s locker room, a restaurant and a medical office staffed by an on-site physician. Mr. Braun’s goal was to “provide comfortable and pleasant surroundings for its workers, of every class, that they may have pleasure in their work and pride in their plant and product.” He took a great deal of pride in the “modern workplace” that he created.

The Granada, the Carmelite Monastery and The Alhambra are an integral part of Alhambra’s story. They inform Alhambrans about what life was like and how people lived and worked during the 1920s – a time of intense growth in our city. They offer a visual history. Their designs were thoughtful. Their materials and workmanship reveal the artistry, industry and aesthetic of the people who built them and the time in which they were built. When we allow historic buildings to be demolished, we sacrifice those touchstones that, by revealing our past, can help to inform decisions about our future.

Alhambra Preservation Group continues its work to protect and preserve Alhambra’s local historic and architectural landmarks and to celebrate their unique and irreplaceable contributions to our city’s community and culture.

A special thank you to Chris Olson, former president and board of member of Alhambra Preservation Group, for her assistance in writing this article.

With COVID-19 turning our world upside down, we’re all looking for ways to occupy our time while we stay safer at home. Why not take advantage of all the free virtual tours available online?

With COVID-19 turning our world upside down, we’re all looking for ways to occupy our time while we stay safer at home. Why not take advantage of all the free virtual tours available online?  As we enter a new decade, many of Alhambra’s homes and buildings will be celebrating their centennials in the 2020s. Here at

As we enter a new decade, many of Alhambra’s homes and buildings will be celebrating their centennials in the 2020s. Here at  United States. And, thanks, in part, to a clever marketing campaign by our Chamber of Commerce that promised a garden paradise, a “City of Homes,” where year-round sunshine offered a healthful climate capable of curing any ailment, thousands of these newcomers settled in Alhambra. Their energy and optimism not only fueled Alhambra’s own growth, but contributed to the development of the entire region.

United States. And, thanks, in part, to a clever marketing campaign by our Chamber of Commerce that promised a garden paradise, a “City of Homes,” where year-round sunshine offered a healthful climate capable of curing any ailment, thousands of these newcomers settled in Alhambra. Their energy and optimism not only fueled Alhambra’s own growth, but contributed to the development of the entire region. by Oscar Amaro, Founder and President, Alhambra Preservation Group

by Oscar Amaro, Founder and President, Alhambra Preservation Group by Barbara Beckley, Alhambra Preservation Group Board of Directors

by Barbara Beckley, Alhambra Preservation Group Board of Directors Arranged through the courtesy of Ladd Jackson, the Estates Director of Hilton & Hyland, which is listing the hilltop castle for $4.9 million, APG members were treated to a one-hour walk and talk – led by Ladd – through the 8,686-square-foot, two story home and its 2.5-acre walled grounds.

Arranged through the courtesy of Ladd Jackson, the Estates Director of Hilton & Hyland, which is listing the hilltop castle for $4.9 million, APG members were treated to a one-hour walk and talk – led by Ladd – through the 8,686-square-foot, two story home and its 2.5-acre walled grounds. Photos were not allowed inside, but members captured memorable photos from the grounds. To see the interior rooms visit the Hilton & Hyland

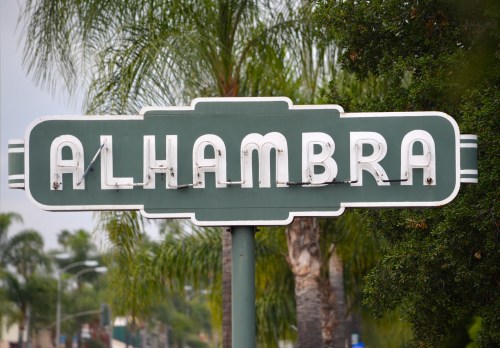

Photos were not allowed inside, but members captured memorable photos from the grounds. To see the interior rooms visit the Hilton & Hyland  Anyone who has lived in Alhambra any length of time has probably caught a glimpse of one of three “Alhambra” signs located at the city’s borders – East Main Street on the border of San Gabriel, West Huntington Blvd on the border of El Sereno and West Valley Blvd at the 710 terminus. The problem is that two of the iconic neon signs haven’t worked for decades and the third sign on West Valley, while still working, has been looking worn out and neglected.

Anyone who has lived in Alhambra any length of time has probably caught a glimpse of one of three “Alhambra” signs located at the city’s borders – East Main Street on the border of San Gabriel, West Huntington Blvd on the border of El Sereno and West Valley Blvd at the 710 terminus. The problem is that two of the iconic neon signs haven’t worked for decades and the third sign on West Valley, while still working, has been looking worn out and neglected. We are pleased that Alhambra’s welcome signs have returned in a blaze of glory. Here’s hoping that they shine bright for generations to come.

We are pleased that Alhambra’s welcome signs have returned in a blaze of glory. Here’s hoping that they shine bright for generations to come. Alhambra Preservation Group strongly urges you to attend the Alhambra City Council meeting on Monday, September 9, 2019 when City Council will have a second reading of an ordinance that was initially intended to institute Rosenberg’s Rules of Order rather than Robert’s Rules of Order at City Council meetings. However, at the August 12 Council meeting when this ordinance had its first reading, Councilman David Mejia proposed two amendments, which included the following:

Alhambra Preservation Group strongly urges you to attend the Alhambra City Council meeting on Monday, September 9, 2019 when City Council will have a second reading of an ordinance that was initially intended to institute Rosenberg’s Rules of Order rather than Robert’s Rules of Order at City Council meetings. However, at the August 12 Council meeting when this ordinance had its first reading, Councilman David Mejia proposed two amendments, which included the following: Throughout the United States, cities both big and small have conducted historic resources inventories to better understand the properties within their communities that are historically, culturally and architecturally significant.

Throughout the United States, cities both big and small have conducted historic resources inventories to better understand the properties within their communities that are historically, culturally and architecturally significant. Many of you may be familiar with Easter eggs. No, not the kind filled with candy that children go hunting for this time of year. The Easter eggs we’re referring to are hidden features, messages or images in a video game. With the holiday weekend upon us, we thought it would be fun to highlight some of Alhambra’s architectural Easter eggs – those architecturally significant structures and/or features that may be easy to miss if you’re not looking for them. Here are just a few – waiting to be found by you!

Many of you may be familiar with Easter eggs. No, not the kind filled with candy that children go hunting for this time of year. The Easter eggs we’re referring to are hidden features, messages or images in a video game. With the holiday weekend upon us, we thought it would be fun to highlight some of Alhambra’s architectural Easter eggs – those architecturally significant structures and/or features that may be easy to miss if you’re not looking for them. Here are just a few – waiting to be found by you! Millard Sheets Murals at Mark Keppel High School – In the late 1930s, as Alhambra’s Mark Keppel High School was being built,

Millard Sheets Murals at Mark Keppel High School – In the late 1930s, as Alhambra’s Mark Keppel High School was being built,  Neon “Alhambra” Welcome Signs – At the western, eastern and southern entrances to the city of Alhambra, you’ll find “Alhambra” neon signs, which welcome visitors to our city. Currently only the southern sign on Valley Blvd. is working. Neon signs and their rich history date back to the early 1900s. The French chemist, inventor and engineer Georges Claude introduced the first neon lamp to the public in 1910; he introduced neon signs to the US in 1923. In addition to its welcome signs, Alhambra has two historic businesses that use neon signs. The Hat on Valley Blvd. and Bun N Burger on Main St. both feature vintage neon signs. Alhambra’s Arts and Cultural Events Committee is considering the restoration of Alhambra’s neon welcome signs. APG applauds this idea. (Alhambra’s neon signs – Huntington Blvd. at the border of El Sereno, Main Street at the border of San Gabriel, Valley Blvd. at the border of Los Angeles)

Neon “Alhambra” Welcome Signs – At the western, eastern and southern entrances to the city of Alhambra, you’ll find “Alhambra” neon signs, which welcome visitors to our city. Currently only the southern sign on Valley Blvd. is working. Neon signs and their rich history date back to the early 1900s. The French chemist, inventor and engineer Georges Claude introduced the first neon lamp to the public in 1910; he introduced neon signs to the US in 1923. In addition to its welcome signs, Alhambra has two historic businesses that use neon signs. The Hat on Valley Blvd. and Bun N Burger on Main St. both feature vintage neon signs. Alhambra’s Arts and Cultural Events Committee is considering the restoration of Alhambra’s neon welcome signs. APG applauds this idea. (Alhambra’s neon signs – Huntington Blvd. at the border of El Sereno, Main Street at the border of San Gabriel, Valley Blvd. at the border of Los Angeles) Joe Candalot & Sons Building – Just east of Alhambra’ neon sign on Valley Blvd. at the terminus of the 710 Freeway, you’ll find a simple non-descript two-story brick building with the words “Joe Candalot & Sons – 1926” imprinted near the roof. In 1899, Sylvestre Dupuy – the original owner of Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle – married Anna Candalot, a young Frenchwoman and accomplished chef. They raised four children – a daughter and three sons – in Alhambra. After the Dupuy’s moved into the Pyrenees Castle in 1927, the couple began developing lots on present-day Valley Blvd. Mr. Dupuy set up his sons in the tire business, naming it Y Tire Sales, which is still located on Valley Blvd. and is still owned by the Dupuy family. Whether this building in southwestern Alhambra was at one time the offices of Y Tire Sales has yet to be proven. And who was Joseph Candalot? Anna Candalot Dupuy’s father? Her brother? We’re still researching this branch of the Dupuy family. But the fact that the Candalot name features prominently on the building’s edifice links it to Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle somehow. (Joe Candalot & Sons Building, 3078 Valley Blvd., Alhambra)

Joe Candalot & Sons Building – Just east of Alhambra’ neon sign on Valley Blvd. at the terminus of the 710 Freeway, you’ll find a simple non-descript two-story brick building with the words “Joe Candalot & Sons – 1926” imprinted near the roof. In 1899, Sylvestre Dupuy – the original owner of Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle – married Anna Candalot, a young Frenchwoman and accomplished chef. They raised four children – a daughter and three sons – in Alhambra. After the Dupuy’s moved into the Pyrenees Castle in 1927, the couple began developing lots on present-day Valley Blvd. Mr. Dupuy set up his sons in the tire business, naming it Y Tire Sales, which is still located on Valley Blvd. and is still owned by the Dupuy family. Whether this building in southwestern Alhambra was at one time the offices of Y Tire Sales has yet to be proven. And who was Joseph Candalot? Anna Candalot Dupuy’s father? Her brother? We’re still researching this branch of the Dupuy family. But the fact that the Candalot name features prominently on the building’s edifice links it to Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle somehow. (Joe Candalot & Sons Building, 3078 Valley Blvd., Alhambra) Former Home Furniture Company Building Façade – As you drive east on Main Street just past Garfield Avenue, look to your left and you’ll discover a building that looks decidedly different than its neighbors. Several years ago, the 1970’s façade of this building was removed and an early 20th century storefront was discovered underneath. This building was the original location of Alhambra’s Home Furniture Company, which was Alhambra’s preeminent furniture store in the early 20th century. Boasting more than 32,000 square feet of furniture display space, the Home Furniture Company saw several owners during its lifetime. Today the façade that remains features decorative pillars and ornamental urns adorned with garlands of fruit and ribbon. (Former Home Furniture Company Building, 43 East Main Street, Alhambra)

Former Home Furniture Company Building Façade – As you drive east on Main Street just past Garfield Avenue, look to your left and you’ll discover a building that looks decidedly different than its neighbors. Several years ago, the 1970’s façade of this building was removed and an early 20th century storefront was discovered underneath. This building was the original location of Alhambra’s Home Furniture Company, which was Alhambra’s preeminent furniture store in the early 20th century. Boasting more than 32,000 square feet of furniture display space, the Home Furniture Company saw several owners during its lifetime. Today the façade that remains features decorative pillars and ornamental urns adorned with garlands of fruit and ribbon. (Former Home Furniture Company Building, 43 East Main Street, Alhambra)