This year we are focusing on 1920s Alhambra. In this issue, we shine the spotlight on three of Alhambra’s neighborhoods that were developed and “grew up” in the 1920s – Emery Park, Mayfair and the Orange Blossom Manor Tracts.

All three of these 1920s neighborhoods include homes that feature the architectural styles that were prevalent in the 1920s – Spanish Colonial Revival, Storybook, American Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, the English Cottage, among others. Architecturally, the 1920s was a time when there was a style for every taste, and all those “styles” can be still be found in present-day Alhambra neighborhoods – nearly a century after they were built.

Emery Park

The official opening day celebration for Emery Park was held on Sunday, February 26, 1922. Emery Park was a brand new subdivision, created from an area west of Fremont Avenue and south of Main Street, that had been annexed to the City of Alhambra in 1908. It had once been known as Dolgeville – Alfred Dolge’s model manufacturing suburb.

More than 1,000 people attended Emery Park’s opening day event, which was sponsored by the real estate development firm of Meyering & Lawrence. Many of them traveled from downtown Los Angeles on buses hired by the company. A free lunch was served as an enticement, and prizes were given away to buyers – handy domestic items that homeowners might need – like sewing machines, rocking chairs, table lamps and coffee percolators.

It must have been quite an impressive sight on that beautiful, late winter day, to see the more than 500 acres of Emery Park from a viewpoint near the top of the hill! One writer described his own experience of seeing the new subdivision for the first time:

“The view was so beautiful it shocked me – shocked me and thrilled me. Below was unfolded a panorama of unforgettable loveliness. It seemed such a different world I had to consult my watch to realize that twenty minutes before we had been held up by a traffic jam at Sixth and Olive. Peaceful Alhambra lay to the right, and far over on the left her autocratic sister, Pasadena, flaunted her charms. A green carpet rolled out from our feet, straight away to the backdrop – the mountain range, over which hung a purple haze. And rising out of this purple was Mt. Baldy, like a white-haired old vet, snowcapped, magnificent.”

Writer Unknown

Twenty-two lots were sold that first afternoon alone. A grading camp was established on site, and work began on the construction of streets and roadways within Emery Park. Poplar Blvd was already paved, but it was widened so that the new tract could be connected to the main business district in Alhambra.

Fast forward nearly a century and many of the homes that were built in Emery Park remain there today. Driving up and down Emery Parks’ streets, one will still find Spanish Revival, Pueblo Revival, Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival and Storybook homes.

Mayfair

Named after one of the most elegant and expensive sections of the city of London, Alhambra’s Mayfair Tract is 63 acres in size, bounded by San Marino Avenue on the north, Valley Boulevard on the south, Garfield Avenue on the east, and 6th Street on the west.

By the 1920s, Mayfair remained one of Alhambra’s last major undeveloped land tracts. The only other large areas of land that still remained were the Graves and Bean orchards in the northeastern portion of the city. With the newly built Garfield Theater just down the street and new businesses popping up all along Valley Boulevard, which had recently changed names from Ocean to Ocean Boulevard, one can understand the appeal of Alhambra’s Mayfair Tract.

One of Mayfair’s most beautiful homes is a Tudor Revival on South 4th Street. Built in 1929, this home, constructed for $5,900, was the first residence built on this block. It most likely served as the tract’s model home.

Today, the Mayfair tract remains one of Alhambra’s most intact historic neighborhoods. Driving through Mayfair, one will see many Spanish Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, and Storybook-styled homes. And, like Emery Park, in Mayfair one will find an attractive mixture of the many architectural styles that were prevalent in the 1920s.

Orange Blossom Manor Tract

The last neighborhood we’re showcasing is the Orange Blossom Manor Tract in northeastern Alhambra and which boasts some of Alhambra’ most beautiful homes. The boundaries of the Orange Blossom Manor Tract are Alhambra Road on the north, Grand Avenue on the south, Almansor Street on the west, and Hidalgo Avenue on the east. Almansor Street between Grand Avenue and Alhambra Road is unofficially known as Alhambra’s Millionaire’s Row with several stunning 1920’s revival-styled homes.

Before it was known as the Orange Blossom Manor Tract this area of land was owned in the late 1800’s by Francis Q. Story, one of Alhambra’ Founding Fathers. Story was a highly successful entrepreneur, who was known as “the Father of the Sunkist Orange” having developed the iconic campaign just after the turn of the 20th century. His citrus orchards stretched from the Alhambra Arroyo eastward toward San Gabriel.

painted by Norman Rockwell

During the 1920’s, Mr. Story began to sell off his many acres of orchard land, and local real estate developers snapped them up to create housing tracts. One of these was the Orange Blossom Manor Tract – so named after the home of famed artist Victor “Clyde” Forsythe and still located at the corner of Alhambra Road and Almansor Street. Some of the most prominent Alhambrans of the 1920’s and 1930’s lived in this exclusive neighborhood.

The varied architectural styles of the homes in this area are reflective of the post World War I period of their construction. The Orange Blossom Manor Tract features a diverse collection of architectural styles, including stately Mid-Atlantic Colonials, sturdy Dutch Colonial Revivals, stunning Spanish Colonial and Mission Revivals, and quaint English Cottages.

In a city that has experienced the destruction of many historic homes, it is important to note that these three Alhambra neighborhoods remain almost completely intact. When you visit Emery Park, Mayfair or the Orange Blossom Manor tracts, you’ll see these neighborhoods almost exactly as they appeared in the late 1920s – a testament both to the excellent quality of the homes and to the commitment of their residents in retaining the original charm and character of these three historic neighborhoods.

Thank you to Chris Olson, past president of Alhambra Preservation Group, for her contribution to this article.

Editor’s Note: This concludes Alhambra Preservation Group’s series on the 1920s. We hope you have enjoyed reading about 1920s Alhambra as much as we’ve enjoyed focusing the spotlight on the beautiful 1920s architecture that can still be found in Alhambra.

Photos courtesy of Alhambra Preservation Group.

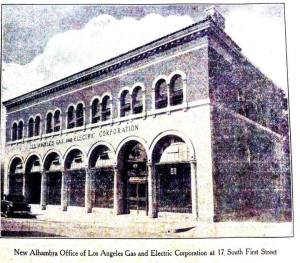

Constructed in 1929 at a cost of $160,000, the building was designed by LA Gas Company architects and engineers to evoke the period of the Italian Renaissance. Arched window and door openings predominate, with a glazed terra cotta base surmounted with varied-colored brick in harmonizing shades.

Constructed in 1929 at a cost of $160,000, the building was designed by LA Gas Company architects and engineers to evoke the period of the Italian Renaissance. Arched window and door openings predominate, with a glazed terra cotta base surmounted with varied-colored brick in harmonizing shades. Newspapers of the day raved about the impressive design and architecture of the building. The first floor contained the main lobby and corporate business offices, manager’s office, investigation room, vault, and distribution department offices.

Newspapers of the day raved about the impressive design and architecture of the building. The first floor contained the main lobby and corporate business offices, manager’s office, investigation room, vault, and distribution department offices.

this type and style of architecture, the convent was described in the Pasadena Post upon its opening on June 24, 1923 as “one of the finest in the United States”. A classically articulated portal of pre-cast concrete defines the monastery’s entrance. The first floor of the convent is defined by loggias at the south and west elevations, which overlook a broad expanse of lawn and garden.

this type and style of architecture, the convent was described in the Pasadena Post upon its opening on June 24, 1923 as “one of the finest in the United States”. A classically articulated portal of pre-cast concrete defines the monastery’s entrance. The first floor of the convent is defined by loggias at the south and west elevations, which overlook a broad expanse of lawn and garden. Alhambra’s Carmelite Monastery was designed by one of Southern California’s most prominent architects. John C. Austin was born in England in 1870, immigrating to California in the 1890’s. He established an architectural practice in Los Angeles in 1895. Austin was very active in local civic affairs, serving as President of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, the Southern California Historical Society, and the Jonathan Club, as well as the California Board of Architectural Examiners. He designed some of the most famous and easily-recognized landmark buildings in the Los Angeles area, many of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Among these distinguished buildings are the Los Angeles City Hall, the Shrine Auditorium, and the Griffith Observatory.

Alhambra’s Carmelite Monastery was designed by one of Southern California’s most prominent architects. John C. Austin was born in England in 1870, immigrating to California in the 1890’s. He established an architectural practice in Los Angeles in 1895. Austin was very active in local civic affairs, serving as President of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, the Southern California Historical Society, and the Jonathan Club, as well as the California Board of Architectural Examiners. He designed some of the most famous and easily-recognized landmark buildings in the Los Angeles area, many of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Among these distinguished buildings are the Los Angeles City Hall, the Shrine Auditorium, and the Griffith Observatory.

C F Braun & Co. moved its international headquarters to Alhambra from San Francisco in 1921. The complex included towering brick walls, 22 buildings and a landscaped plaza on 36 acres. The primary building material for this “modern office complex” was brick – all purchased from the same San Francisco manufacturer. Braun was a practical man, an engineer, who didn’t hesitate to move or modify buildings — or to build new ones — according to the nature of the work in which the company was involved and the functional needs of its various manufacturing projects. The significance — and the beauty — of this campus is that, through dozens of modifications and 92 years of operation, purposeful attention to architectural character and detail has preserved the integrated whole.

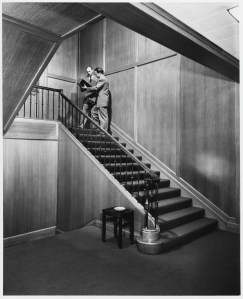

C F Braun & Co. moved its international headquarters to Alhambra from San Francisco in 1921. The complex included towering brick walls, 22 buildings and a landscaped plaza on 36 acres. The primary building material for this “modern office complex” was brick – all purchased from the same San Francisco manufacturer. Braun was a practical man, an engineer, who didn’t hesitate to move or modify buildings — or to build new ones — according to the nature of the work in which the company was involved and the functional needs of its various manufacturing projects. The significance — and the beauty — of this campus is that, through dozens of modifications and 92 years of operation, purposeful attention to architectural character and detail has preserved the integrated whole. C F Braun & Co.’s interior offices featured wood paneling and were “pleasingly appointed and well-lighted” as described in a promotional brochure. It had every amenity needed for a modern manufacturing plant including a state-of-the-art engineering library, woman’s lounge, men’s locker room, a restaurant and a medical office staffed by an on-site physician. Mr. Braun’s goal was to “provide comfortable and pleasant surroundings for its workers, of every class, that they may have pleasure in their work and pride in their plant and product.” He took a great deal of pride in the “modern workplace” that he created.

C F Braun & Co.’s interior offices featured wood paneling and were “pleasingly appointed and well-lighted” as described in a promotional brochure. It had every amenity needed for a modern manufacturing plant including a state-of-the-art engineering library, woman’s lounge, men’s locker room, a restaurant and a medical office staffed by an on-site physician. Mr. Braun’s goal was to “provide comfortable and pleasant surroundings for its workers, of every class, that they may have pleasure in their work and pride in their plant and product.” He took a great deal of pride in the “modern workplace” that he created. Many of you may be familiar with Easter eggs. No, not the kind filled with candy that children go hunting for this time of year. The Easter eggs we’re referring to are hidden features, messages or images in a video game. With the holiday weekend upon us, we thought it would be fun to highlight some of Alhambra’s architectural Easter eggs – those architecturally significant structures and/or features that may be easy to miss if you’re not looking for them. Here are just a few – waiting to be found by you!

Many of you may be familiar with Easter eggs. No, not the kind filled with candy that children go hunting for this time of year. The Easter eggs we’re referring to are hidden features, messages or images in a video game. With the holiday weekend upon us, we thought it would be fun to highlight some of Alhambra’s architectural Easter eggs – those architecturally significant structures and/or features that may be easy to miss if you’re not looking for them. Here are just a few – waiting to be found by you! Millard Sheets Murals at Mark Keppel High School – In the late 1930s, as Alhambra’s Mark Keppel High School was being built,

Millard Sheets Murals at Mark Keppel High School – In the late 1930s, as Alhambra’s Mark Keppel High School was being built,  Neon “Alhambra” Welcome Signs – At the western, eastern and southern entrances to the city of Alhambra, you’ll find “Alhambra” neon signs, which welcome visitors to our city. Currently only the southern sign on Valley Blvd. is working. Neon signs and their rich history date back to the early 1900s. The French chemist, inventor and engineer Georges Claude introduced the first neon lamp to the public in 1910; he introduced neon signs to the US in 1923. In addition to its welcome signs, Alhambra has two historic businesses that use neon signs. The Hat on Valley Blvd. and Bun N Burger on Main St. both feature vintage neon signs. Alhambra’s Arts and Cultural Events Committee is considering the restoration of Alhambra’s neon welcome signs. APG applauds this idea. (Alhambra’s neon signs – Huntington Blvd. at the border of El Sereno, Main Street at the border of San Gabriel, Valley Blvd. at the border of Los Angeles)

Neon “Alhambra” Welcome Signs – At the western, eastern and southern entrances to the city of Alhambra, you’ll find “Alhambra” neon signs, which welcome visitors to our city. Currently only the southern sign on Valley Blvd. is working. Neon signs and their rich history date back to the early 1900s. The French chemist, inventor and engineer Georges Claude introduced the first neon lamp to the public in 1910; he introduced neon signs to the US in 1923. In addition to its welcome signs, Alhambra has two historic businesses that use neon signs. The Hat on Valley Blvd. and Bun N Burger on Main St. both feature vintage neon signs. Alhambra’s Arts and Cultural Events Committee is considering the restoration of Alhambra’s neon welcome signs. APG applauds this idea. (Alhambra’s neon signs – Huntington Blvd. at the border of El Sereno, Main Street at the border of San Gabriel, Valley Blvd. at the border of Los Angeles) Joe Candalot & Sons Building – Just east of Alhambra’ neon sign on Valley Blvd. at the terminus of the 710 Freeway, you’ll find a simple non-descript two-story brick building with the words “Joe Candalot & Sons – 1926” imprinted near the roof. In 1899, Sylvestre Dupuy – the original owner of Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle – married Anna Candalot, a young Frenchwoman and accomplished chef. They raised four children – a daughter and three sons – in Alhambra. After the Dupuy’s moved into the Pyrenees Castle in 1927, the couple began developing lots on present-day Valley Blvd. Mr. Dupuy set up his sons in the tire business, naming it Y Tire Sales, which is still located on Valley Blvd. and is still owned by the Dupuy family. Whether this building in southwestern Alhambra was at one time the offices of Y Tire Sales has yet to be proven. And who was Joseph Candalot? Anna Candalot Dupuy’s father? Her brother? We’re still researching this branch of the Dupuy family. But the fact that the Candalot name features prominently on the building’s edifice links it to Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle somehow. (Joe Candalot & Sons Building, 3078 Valley Blvd., Alhambra)

Joe Candalot & Sons Building – Just east of Alhambra’ neon sign on Valley Blvd. at the terminus of the 710 Freeway, you’ll find a simple non-descript two-story brick building with the words “Joe Candalot & Sons – 1926” imprinted near the roof. In 1899, Sylvestre Dupuy – the original owner of Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle – married Anna Candalot, a young Frenchwoman and accomplished chef. They raised four children – a daughter and three sons – in Alhambra. After the Dupuy’s moved into the Pyrenees Castle in 1927, the couple began developing lots on present-day Valley Blvd. Mr. Dupuy set up his sons in the tire business, naming it Y Tire Sales, which is still located on Valley Blvd. and is still owned by the Dupuy family. Whether this building in southwestern Alhambra was at one time the offices of Y Tire Sales has yet to be proven. And who was Joseph Candalot? Anna Candalot Dupuy’s father? Her brother? We’re still researching this branch of the Dupuy family. But the fact that the Candalot name features prominently on the building’s edifice links it to Alhambra’s Pyrenees Castle somehow. (Joe Candalot & Sons Building, 3078 Valley Blvd., Alhambra) Alhambra’s Millionaire’s Row – In the early 20th century, many cities had neighborhoods that came to be known as “Millionaire’s Row.” These were streets lined with mansions owned by wealthy and influential city leaders. Alhambra was no different. During the 1920s and 30s, Alhambra’s elite lived on North Almansor Street in the Orange Blossom Manor tract, which featured homes with revivalist architectural styles ranging from English Tudor to American Colonial, from Dutch Colonial to Spanish Colonial. The homes were owned by such Alhambra luminaries as Victor Clyde Forsythe, renowned southwest Plein Air painter; Frank Olson, a lumberman who owned Olson Lumber and whose stunning English Tudor Revival home remains today; and Elmer Bailey, an experienced citrus orchardist who established the Golden Pheasant brand. Homes on Alhambra’s Millionaire’s Row have been featured on home tours and in movies. (Alhambra’s Millionaire’s Row, North Almansor Street north of Main Street)

Alhambra’s Millionaire’s Row – In the early 20th century, many cities had neighborhoods that came to be known as “Millionaire’s Row.” These were streets lined with mansions owned by wealthy and influential city leaders. Alhambra was no different. During the 1920s and 30s, Alhambra’s elite lived on North Almansor Street in the Orange Blossom Manor tract, which featured homes with revivalist architectural styles ranging from English Tudor to American Colonial, from Dutch Colonial to Spanish Colonial. The homes were owned by such Alhambra luminaries as Victor Clyde Forsythe, renowned southwest Plein Air painter; Frank Olson, a lumberman who owned Olson Lumber and whose stunning English Tudor Revival home remains today; and Elmer Bailey, an experienced citrus orchardist who established the Golden Pheasant brand. Homes on Alhambra’s Millionaire’s Row have been featured on home tours and in movies. (Alhambra’s Millionaire’s Row, North Almansor Street north of Main Street) Former Home Furniture Company Building Façade – As you drive east on Main Street just past Garfield Avenue, look to your left and you’ll discover a building that looks decidedly different than its neighbors. Several years ago, the 1970’s façade of this building was removed and an early 20th century storefront was discovered underneath. This building was the original location of Alhambra’s Home Furniture Company, which was Alhambra’s preeminent furniture store in the early 20th century. Boasting more than 32,000 square feet of furniture display space, the Home Furniture Company saw several owners during its lifetime. Today the façade that remains features decorative pillars and ornamental urns adorned with garlands of fruit and ribbon. (Former Home Furniture Company Building, 43 East Main Street, Alhambra)

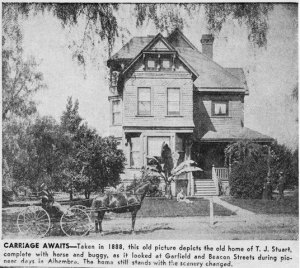

Former Home Furniture Company Building Façade – As you drive east on Main Street just past Garfield Avenue, look to your left and you’ll discover a building that looks decidedly different than its neighbors. Several years ago, the 1970’s façade of this building was removed and an early 20th century storefront was discovered underneath. This building was the original location of Alhambra’s Home Furniture Company, which was Alhambra’s preeminent furniture store in the early 20th century. Boasting more than 32,000 square feet of furniture display space, the Home Furniture Company saw several owners during its lifetime. Today the façade that remains features decorative pillars and ornamental urns adorned with garlands of fruit and ribbon. (Former Home Furniture Company Building, 43 East Main Street, Alhambra) 403 South Garfield – Easily Alhambra’s most recognizable Victorian home, this three-story Queen Anne Victorian home has stood at 403 South Garfield since the mid-1880s and was home to multiple families before it was even 50 years old. This house was home to the owner of a printing company, a teamster, a salesman and served as a boarding house called The Garfield during the 1920s. Listed in the 1984 Alhambra Historic Resources Survey, this home would qualify as local landmark status. A little known fact is that famed San Gabriel Mountains conservationist and hiker Will Thrall lived across the street from this home at 400 South Garfield during the early 20th century.

403 South Garfield – Easily Alhambra’s most recognizable Victorian home, this three-story Queen Anne Victorian home has stood at 403 South Garfield since the mid-1880s and was home to multiple families before it was even 50 years old. This house was home to the owner of a printing company, a teamster, a salesman and served as a boarding house called The Garfield during the 1920s. Listed in the 1984 Alhambra Historic Resources Survey, this home would qualify as local landmark status. A little known fact is that famed San Gabriel Mountains conservationist and hiker Will Thrall lived across the street from this home at 400 South Garfield during the early 20th century. 300 North Granada Avenue – This was the home of one of Alhambra’s founding fathers – James DeBarth Shorb – and his large family. James DeBarth Shorb’s wife was Maria, the eldest daughter of Alhambra’s founder, Don Benito Wilson. Rumor has it that this home may have been moved in the early 20th century from San Marino to the home’s current location on North Granada. Built in 1888, this house, which was built in the Italianate style, features characteristics that one would find in this Victorian-era architecture. The two-story house is sheathed in shiplap siding and features a truncated roof with bracketed cornices at the eaves line.

300 North Granada Avenue – This was the home of one of Alhambra’s founding fathers – James DeBarth Shorb – and his large family. James DeBarth Shorb’s wife was Maria, the eldest daughter of Alhambra’s founder, Don Benito Wilson. Rumor has it that this home may have been moved in the early 20th century from San Marino to the home’s current location on North Granada. Built in 1888, this house, which was built in the Italianate style, features characteristics that one would find in this Victorian-era architecture. The two-story house is sheathed in shiplap siding and features a truncated roof with bracketed cornices at the eaves line. 502 North Story Place – Francis and Charlotte Story built the home at 502 North Story Place in 1883. Its matching carriage house can be found a few doors down Story Place. Francis Q. Story was among Alhambra’s first leaders and played a huge part in the success of California’s fledgling citrus industry by creating the Sunkist brand of oranges that endures today. Mrs. Story was key in establishing Alhambra’s first library.

502 North Story Place – Francis and Charlotte Story built the home at 502 North Story Place in 1883. Its matching carriage house can be found a few doors down Story Place. Francis Q. Story was among Alhambra’s first leaders and played a huge part in the success of California’s fledgling citrus industry by creating the Sunkist brand of oranges that endures today. Mrs. Story was key in establishing Alhambra’s first library. the corner of present day Almansor Street and Alhambra Road! Mr. Story’s citrus orchards stretched from the arroyo on the east to present day Main Street on the south.

the corner of present day Almansor Street and Alhambra Road! Mr. Story’s citrus orchards stretched from the arroyo on the east to present day Main Street on the south. 1306 West Pine Street – Located in the northwest corner of Alhambra, on the border of South Pasadena, this two-story Foursquare home was built in 1905 and was the original home of Adolph Graffen, an orchardist whose land holdings included the area from this home south to Alhambra Road and east to Atlantic Boulevard. A fun fact is that when Mr. Graffen subdivided his land in the early 20th century, present-day Marguerita Avenue was named after his daughter, Margie.

1306 West Pine Street – Located in the northwest corner of Alhambra, on the border of South Pasadena, this two-story Foursquare home was built in 1905 and was the original home of Adolph Graffen, an orchardist whose land holdings included the area from this home south to Alhambra Road and east to Atlantic Boulevard. A fun fact is that when Mr. Graffen subdivided his land in the early 20th century, present-day Marguerita Avenue was named after his daughter, Margie. of present day Stoneman Avenue and Elgin Street. Elgin, Illinois was the birth place of Claude Adams and this may account for the naming of this small street in Alhambra. This was the home of Samuel and Emma Crow in the early 20th century. The Crows, in partnership with William Drake, owned Crow and Drake Grocers, which was located at 4 East Main Street, catty corner from the Alhambra Hotel. No doubt they did a booming business as “Dealers in Groceries, Hardware, Tinware, Provisions, Fruit, Flour and Feed” as their 1903 advertisement boasted.

of present day Stoneman Avenue and Elgin Street. Elgin, Illinois was the birth place of Claude Adams and this may account for the naming of this small street in Alhambra. This was the home of Samuel and Emma Crow in the early 20th century. The Crows, in partnership with William Drake, owned Crow and Drake Grocers, which was located at 4 East Main Street, catty corner from the Alhambra Hotel. No doubt they did a booming business as “Dealers in Groceries, Hardware, Tinware, Provisions, Fruit, Flour and Feed” as their 1903 advertisement boasted. 2114 and 2118 San Clemente Avenue – Tucked away on the corner of San Clemente Avenue and Date Avenue, just west of Alhambra’s Granada Park is a pair of transitional Victorian homes built in 1905 and 1910 respectively. Transitional Victorians were popular during this time and often included a mix of Victorian and Arts and Crafts characteristics. Built long before the Midwick Country Club was constructed, the owners of these homes were probably two of Alhambra’s earliest farmers or orchardists.

2114 and 2118 San Clemente Avenue – Tucked away on the corner of San Clemente Avenue and Date Avenue, just west of Alhambra’s Granada Park is a pair of transitional Victorian homes built in 1905 and 1910 respectively. Transitional Victorians were popular during this time and often included a mix of Victorian and Arts and Crafts characteristics. Built long before the Midwick Country Club was constructed, the owners of these homes were probably two of Alhambra’s earliest farmers or orchardists.